I recently read a pedagogical blurb which said “shaping the learning”.

Apparently the words shape and shaping are used throughout the Australian national early years documents, including the educational leader resource documents - so it makes sense that these words are being used.

But it’s a word that makes me, personally, uncomfortable. it makes me think of a lump of clay that is being shaped into something - whether that be the child, the learning or the teachers/teaching under leadership. It means, to me, there is a clear agenda of what the shape should be in order for it to be “shaped”.

My ongoing decolonising work has included deep thinking about the words I use and the undertones they have. I have shifted from words like foundation to roots - taking inspiration from nature and a more organic way of evolving within an ecosystem, instead of the human-made foundation that requires us to know what we are building in order to get the foundations right. I think my childhood city taught me a lot about this… I come from York, which has the largest cathedral north of the alps at its heart. The centuries old building risked collapse because the central tower was bigger and heavier than the foundations could hold - originally built for a much smaller building. So they needed to be re-enforced, and windows needed metal supports to prevent them buckling and falling out. It’s a lot of expensive and invasive procedures that need to be done (mind you, they did discover the remains of the Roman headquarters while doing this).

Roots grow in tact with the plant. And it is for this reason I want to focus on roots rather than foundations. What can I do, in my capacity as an educator/playworker/parent that nourishes the roots of each child, and allows the roots to connect with each other - the mycelium.

Tending to the well-being of the roots allows the children to take the shape they want to be - rather than being forced to be the shape they are expected to be - which is often harmful when the normative is too narrow. We should be providing opportunities for children to test out multiple shapes of being so that they can choose the one/ones that suit them best (because we might need multiple shapes simultaneously and/or change over time).

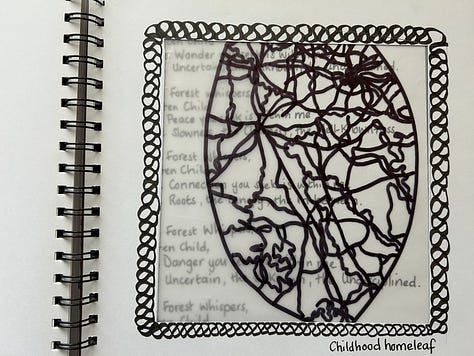

My own decolonising process has included walking the land and creating art.

The first image, “The Weary Pine” is inspired by a tree that I take a photo of every time I walk past it. Always spending some time to being there, like with an old friend.

I look at how this tree grows. The roots wrapped around the rock, going all the way down to seek the soil, nutrition and connection with the rest of the forest. I also see how the tree bends in order to find balance. The tree has found their own shape in order to grow.

If we had told this tree that to be a tree they needed to grow straight, it would have resulted in the tree being forced to grow in a way that would make them constantly vulnerable to the earthly elements - especially wind - instead of putting in their energy to grow to in a manner they could thrive. Or the risk of being seen as a problem of they continued to respond to the nature of the land they are growing on.

And I think this is the case very often. We want children to be like the perfect straight trees in plantations* rather than the complexity offered in old growth forests.

In the final chapter of my book “The Original Learning Approach” I write

I think of the tomato plant that my husband placed on our windowsill in late spring. The warm and sunny conditions were perfect for it to grow fast. The problem was that the tomato plant put all its energy into growing tall but failed to put energy into growing strong. It did not take long before it was unable to support itself. I decided to move it onto our balcony, where the nights were still a bit cool, as I had read research about how the wind made trees strong. Apparently, as trees adapt to their natural habitat, they grow strong rather than tall in very windy areas, as the wind forces the tree to expend energy to ensure the trunk, branches, and roots can withstand the wind and not just grow upward toward the light. I applied this knowledge to the tomato plant. It needed some adversity to grow stronger. I used supports to scaffold the plant, as it was not strong enough at first to manage alone. But after a few weeks of dancing in the wind I could see the tomato plant was now investing in strength rather than just height as the stalks grew sturdier.

As educators we need to create a habitat that allows the children, and ourselves, to grow sustainably. The system might put pressure on schools to be the fastest or the tallest or the best, but this is not always the most sustainable approach to learning, understanding, and well-being.

Had I not moved the tomato plant so that it could grow stronger, then it would not have been able to carry the weight of its own tomatoes. The balcony habitat offered the right amount of complexity that allowed the tomato plant to be autonomous, although during hot, dry weather we helped it out by watering.

This is what we should be doing within the play-ecosystem. We create optimal habitats so the children can become autonomous in their play and learning, while remembering we need to respond to the children's interactions with each other, and the ecosystem, in order for them to grow strong. Planning challenges and adversity that provides complexity and strength is important. Equally important is understanding when there is too much adversity, and we risk uprooting or breaking the learning branches, such as when we make children learn to write before they are cognitively, emotionally, and physically ready. In reality each child is ready at different times, probably ranging from age 3 to 12. Deciding all five year olds need to start learning to write in the same month regardless of when in the year they were born, is to me highly disrespectful of not only the children but also all the researchers and teachers that are constantly explaining how children actually learn.

Management, leaders, policy-makers, and politicians all are responsible for providing a safe, rich habitat that allows educators to become strong and able to sustainably adapt and change. Hothousing teacher training and educational reforms can be just as damaging as hothousing children, where the focus is on the product rather than the process.

I think hothousing is closely related to shaping… because there is a clear product in mind and wellbeing is only being considered in relation to fulfilling the products criteria rather than the actual needs to thrive and experience well-being. Sometimes being bent is being true to one’s own nature, and being straight is harmful.

In the Imagination chapter of my book I wrote

If we view the children’s imagination as seeds that grow through play, and our role as educator is picking the flower, which is to say the idea, that emerges from that seed, in order to create a curriculum, then we must remember that we adults have created the soil in which the children are planting their seeds. If we are not tending to the well-being of the soil, with an awareness of the ecology of imagination, play, and understanding, then the ground might not be fertile enough to plant seeds, or too hard for the seeds to break the surface, or only suitable for a limited number of (adult) preselected seeds. An emergent curriculum, for example, comes from the children, but can be limited by what the children feel they are permitted to share or express.

Adults need to be aware of how words, actions, attitudes, the design of the space and the choices of resources will influence what seeds the children feel they are allowed or feel safe to plant.

Context

A sense of belonging

Feelings of safety and being valued

Bias and stereotypes

All of these will affect a child’s choices and ability to plant seeds as well as what flowers will emerge. Which seeds will be cultivated, and which ones will whither through lack of care, awareness, or knowledge? Which ones will eventually get picked?

This is why, in the Original Learning Approach, I write about being play responsive rather than play-based. The latter I feel allows adults to “shape” the garden to be child-friendly and pedagogical from the perspective of how adults view the child and play. This means that if their view of a child is as a lump of clay needing to be shaped, or an empty bucket needing to be filled, or of a child that cannot be trusted, or that certain play needs are prohibited because the adults don’t feel comfortable… the garden/setting provided for the children will be shaping them to not be empowered and to feel ashamed of their play needs. Instead, if we are collaborating with nature (rather than taming it and striving for monocultures) by ensuring there is time, space, and opportunity for autonomous play - which we take notice of in order to inform us how to teach - then diversity has a better chance to not only survive but thrive and evolve within such a play ecosystem.

The word shaping, when in the context of a garden, makes me think of French garden design which is extremely controlled by humans to the point that many plants are not allowed their natural shape but are constantly pruned and trimmed to achieve the desired look.

So, my personal opinion is that we should be shifting from shaping within pedagogy as a part of our decolonising process. And searching for other words to describe the process of nurturing the play and learning ecosystem.

* Plantation is a grand-scale monoculture farming approach which is historically connected to slavery and colonialism (these days these words have been replaced with exploitation and capitalism). It is a word that is used around the world to describe a farming method. In my book I use the term tree-farm, as you see in the quote below as my USA publishers felt the word plantation was too sensitive to use in USA. Having spent time in Massachusetts earlier this year having respectfully changed the word in my book, I was shocked to be staying in the Colonial Inn and to constantly read signs describing the “Colonisers” as freedom fighters. It is constantly interesting to see the decolonising processes and how they can evolve in some areas and not in others.

Teaching just one way to weave threads would be like saying the forest is only trees and ignoring everything else that dwells there, living and nonliving. And sadly, many educational institutions are more like tree farms than forests… rows of monoculture trees, farmed to produce the highest yield of a specified product. Being different in such a culture reduces productivity, and therefore everything is done to correct that. Of course, this is short-term thinking. Life-long learning comes from diversity, people, perspectives, approaches and so on, and learning to understand how to nurture the play-ecosystem, not control or manipulate it.